With Your Shield – Or On It

The role of leaders to develop grit in employees and direct reports

“Fear is a reaction. Courage is a decision.” — Winston Churchill

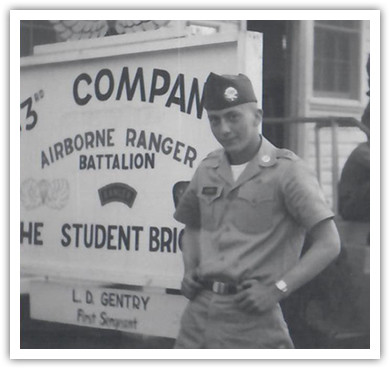

In 1963, on the anniversary of D-Day for World War II, my father enlisted in the army and then became a Green Beret in the Special Forces. He later volunteered to go to Vietnam. But to this day, he remembers the morning that he left for boot camp and his mother’s parting words to him: “With your shield or on it, Phil.”

“With your shield or on it,” she said.

To put that in context, you should understand: Lucia had been an army nurse who served under General Patton in North Africa in World War II. She went with the troops as a triage nurse during the invasion of North Africa and ended the war in Germany. The import of what she said in that moment made an impression on my father that lasted a lifetime. As dad rode the bus to Fort Benning for Jump School and Parachute Training there was no way he was going to let her down.

Jump School training in 1963 was a proving ground. Training in the heat and humidity, together with the physical exertion was exhausting. The dropout rate approached 50%. One tactic of Jump School training instructors was to single out a man on the squad and make an example of him to the others. This was meant to inspire obedience and teach lessons.

My father, Phil, was that man.

At one point during a particularly brutal day, Phil collapsed and briefly lost consciousness. It’s no wonder: the Sergeant in charge of training had withheld water and salt tablets and provided no break in the training all morning. The stated objective of this treatment was to make you quit. While Phil lay there, partly delirious, he heard the Lieutenant say to the Sergeant, “you better not kill that man out of spite, Sergeant.” This tactic continued on and off for over a week and a half.

It would have been 10 days made easier for my father if he had just quit. He could have simply given up on Jump School and the Green Berets and went back to being a private in the regular army.

Later, at the graduation ceremony, the Sergeant looked Phil in the eye and asked him one question: “Why didn’t you quit, Private?”

His answer was short and simple. “My mother was a triage nurse under Patton, Sir. She said to come home with my shield or on it. I wasn’t going to let her down.”

The Sergeant grinned. “Smart woman,” he said, and continued the inspection.

Grit and its Importance to Success

Grit is defined as “firmness of mind or spirit; unyielding courage in the face of hardship or danger.” I would say that Jump School at Fort Benning was my father’s grittiest experience, but it was likely not his last. According to research by Angela Duckworth, gritty people tend to stick to their commitments and see them through – sometimes at great cost.

“Effort matters – everybody knows that effort matters,” says Duckworth. “What was revelatory to me was how much it matters.”

You may be able to relate from your own experience. We all may know the student we grew up with who was just “a natural,” who may have appeared to not need to study as hard; or an athlete whose talent was obvious and put him or her at the top of competition rankings.

And then we may also remember those who had less natural talent but made up for it – and even exceeded the achievements of those with “natural talent” – by studying harder, practicing longer, and sticking with it after others quit.

In short, they have higher grit: the passion and perseverance to forge ahead.

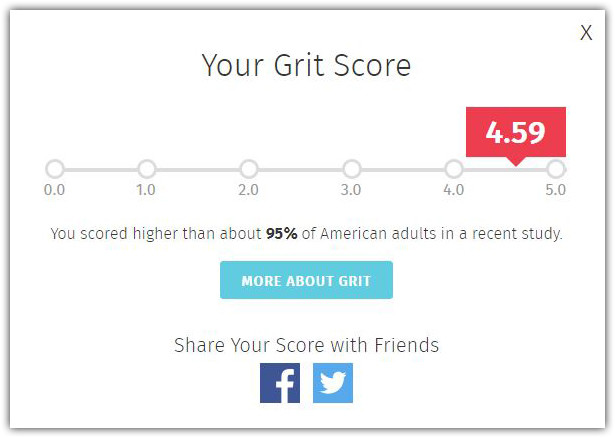

You can measure your own level of grit by taking a short online test at the following link: http://angeladuckworth.com/grit-scale/.

Grit. Can It Be Learned?

You may have heard of the 10,000 Hour Rule, which postulates that it takes experts about that much time to become an expert in their field of study. Olympic athletes, doctoral graduates, and leaders of industry may indeed have spent 10,000 hours becoming the best at what they do. But I believe that grit is what propels them to forge ahead.

I also believe that grit can be learned. But if grit can be learned, it may also be destroyed.

Grit can be learned. But it may also be destroyed.

As leaders and especially as parents, I believe we should encourage the development of grit in our children and employees. And above all else, we must guard against killing the teaching of grit, because it is such a key component of what makes for success in business and in life.

The Danger of “Everybody is a Winner”

Like many parents, my wife and I enrolled our sons in soccer as an early way for them to learn lessons in teamwork, physical fitness, and yes, grit and perseverance. There were many seasons when the last thing I wanted to do as a parent was to stand on the sidelines of the soccer field in rain that was blowing sideways. And there were days when our sons would complain about having to go to soccer practice. But grit isn’t selective; you don’t develop grit by quitting. So we made them stick it out. And they got better.

But one season was particularly competitive and their team didn’t win. It wasn’t even close. We’re talking a win/loss record of 1-in-9 games. It was demoralizing even for the parents who had racked up many a weekend of sideways rain only to lose.

I was shocked when the coach stood up at the last team gathering and told all the athletes that “everyone is a winner.” I expected it to some degree, as the kids were still young. We didn’t want them to be crushed by defeat. An inspiring speech may help. We wanted them to find the motivation to practice harder during the off season and come back next year prepared to compete.

But then they handed out trophies to every single player. The trophies were the same size as the winning team nearby. I remember the look on my son’s face as he tossed the trophy on the seat next to him during the drive home. And the next year, he didn’t sign up to play soccer. He was done.

There are three reasons why this popular method of teaching kills the development of grit.

- First, “everyone is a winner” kills motivation. If everyone gets a medal, what’s the point of striving to win?

- Second, it fails to teach how to deal with failure. Tasting the bitterness of defeat is a defining moment. Learning how to deal with that loss and then get up to fight another day is an important life skill.

- Last, “everyone is a winner” creates unrealistic expectations in life. My wife and I used to joke, “what happens when this generation runs for President? Will everyone win?”

Performance is an Outcome

Of course, I was being facetious about everyone winning when they run for President. But the fact is that the 80/20 Rule (also known as the “Pareto Principle“) is alive and well in many areas of business and life. Not because the deck is stacked, but because grit, perseverance, and effort determine the winners – and to the victor go the spoils.

Alternatives to teaching like a Jump School Sergeant abound, and teaching grit does not have to be harsh. Healthy competition can bring out the best in people, and that goes for our kids as well as our employees.

Teaching grit does not have to be harsh.

Duckworth has developed information about how to teach grit that is worth checking out. The recommendations that work for teachers in the classroom apply equally to teaching grit in business with your direct-reports. Key takeaways:

- Set a goal for the employee to practice

- The employee should practice with 100% focus

- Give feedback and allow time for the employee to reflect

- Rinse and repeat

Wynton Marsalis Teaches Expert Practice for Grit

Have We as a Society Become Overprotective?

An unequivocal “yes!” in my opinion. My generation practically invented the practice of “Helicopter Parenting,” and the coach who handed out the trophies to the losing team was like me, another Gen X’er. As well-intentioned as he may have been, parents, teachers, and yes, even employers have gravitated increasingly toward protectionism and egalitarianism at the cost of murdering the development of grit.

When my family moved to a new neighborhood about a dozen years ago, my son immediately went out and made friends with the other kids on the block. It was only three weeks later that I got a panicked call from a parent down the street, calling me about something my son had done while visiting her house.

She quickly relayed that she was very sorry, had only turned her back for a minute, but she wanted to tell me first so that I would know…

*Gasp*, Aidan had taken a drink from the garden hose.

The inherent concern of parenting is to always worry about one’s children, but when the desire to protect treads into the effect of sheltering, it makes me worry about the future of our society.

In business, as managers, how often have we sheltered our employees?

- By assigning a group project and then failing to recognize leadership that emerges out of fear that those who didn’t step up to leadership might feel left out?

- By not recognizing high achievers because other team members made contributions, but at a lower level of performance?

I have a strong personal preference for meritocracy. But I see increasing levels of egalitarianism creeping into the business world as leaders fear that recognizing top-performers may demotivate broad ranks of employees. What is the effect upon developing the necessary level of grit in our employees to ensure organizational success? What is the answer? I don’t think it is “trophies for everyone!” Do you?

I don’t think the answer is “trophies for everyone!”

Hard work and the passionate pursuit of excellence can only thrive in organizations when the spotlight of success is recognized and rewarded. In the majority of cases, grit is a key ingredient that led to achievement – and it should be recognized, encouraged, and rewarded.

The Role of the Rite of Passage

Jump School was a defining moment for my father. It served as a rite of passage that proved to him that he had the reserves to reach down deep and stand up again – even when the going got tough. The Master Sergeant did not break him and that knowledge stuck with him when future setbacks got in his way.

The importance of rites of passage has been studied, and they vary by culture. In a comparison conducted by Sherri McCarthy-Tucker and Luciana Karine de Souza (2010), they found the following:

- U.S. adolescents cited financial independence and military service as the major indicators of adult status;

- Brazilian youth cited the ability to make important decisions independently from family and to take responsibility for others, such as children, aging parents, or a spouse; and

- Malaysian youth considered completion of education and achieving physical maturity as rites of passage.

In my case, I remember the feeling of achievement that came from completing a summer job in high school on a commercial fishing boat in Alaska. I was 2,000 miles from home and it was my rite of passage at 17. It was an experience straight out of the TV show “Deadliest Catch,” and served as such a formative experience for me that I wrote a college essay about it titled “King of the Deck” that was published my freshman year in college.

Later, as a parent, however, I looked back on my commercial fishing experience and advised my sons against doing the same thing. Was I being protectionist? Yes, absolutely. It was dangerous work.

But the development of grit isn’t something that can be postponed until adulthood. Parents need to encourage the development of grit as early as they can. And employers need to recognize that egalitarian policies can demotivate their top-performers in ways that inhibit organizational success.

We as a society cannot afford that. And we as managers and coaches cannot afford to stunt the development of grit in our direct reports.

Good luck and best wishes as you implement feedback loops to encourage grit in those you influence.

About the author: David Eldred is the President and Chief Brand Technologist for Sine Cera Marketing.